You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

Universal materials improve efficiency and streamline procedures, increase clinical success with predictable and easy-to-use materials, simplify workflow and consolidate materials to help save time and money, are not technique sensitive, and offer multiple applications, indications, and continuity within multiple materials. Based on the author's opinion and practice, using materials that have universal indications, universal compatibility, along with simplified steps and ease of use, will reduce the number of materials needed in the dental office and improve the efficiency and time-effectiveness of procedures.

Some examples of universal composite systems are Filtek by 3M, TPH Spectra ST by Dentsply Sirona, SimpliShade by Kerr, and OmniChroma by Tokuyama Dental America.

Universal composites allow practitioners to consolidate the number of shades and anterior and posterior composites to keep on hand. The universals of different manufacturers mentioned above run from one shade and one accessory to eight shades with two accessories.

Understanding how light reflects off enamel allows the practitioner to replicate it within any resin material. Lower wavelength light has a more diffuse reflection pattern off enamel, and higher wavelength light has more of a specular, crisp, defined reflection pattern. Specular reflection is light reflected from a smooth surface at a definite angle; diffuse reflection is produced by rough surfaces that tend to reflect light in all directions (Figure 1).1 Surface texture and wavelength therefore go hand in hand (Figure 2).2 Different hues or wavelengths cast different reflections, and universal materials manipulate this, having a chameleon effect.3

A pink opaquer may give internal warmth, but it is advisable to use it sparingly and cautiously because if too much is applied it can show through and be too opaque. Some universals may be too sticky and too tacky on the instrument. There may be high viscosities and low viscosities available and the practitioner may prefer one or the other, but sometimes both are needed. Some may be too translucent. Some may need a blocker. Consider a universal that provides a firm, high viscosity when pressing firmly on the composite but that also allows a smooth, low-viscosity brushing effect. Also look for universals with nanoparticles that offer high polishability, wear, durability, and radiopacity. Universals that allow the practitioner to simplify overhead by reducing inventory are most desirable.

The blending effect is used so that the restorations appear invisible and the composite blends within tooth structure. Sometimes odd colors are necessary, but the practitioner may not have them on hand, so it is good that universals may allow the blending of shades.

A common failure of some universals is poor long-term wear and strength, so the practitioner should look for one that promises better resistance to chipping and fracture over time.4

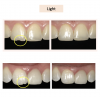

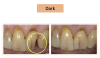

Figure 3 through Figure 5 show some cases the author completed with light, medium, and dark shades. On one of the light-shade cases (Figure 3), the minimal size of the fracture prohibited the use of multiple shades and building in a translucent layer as one could in a larger chipped area, which allows for building in multiple layers. The author used one shade without a blocker, which brought out the natural beauty. In a medium-shade case, a Class III restoration was indicated (Figure 4). The top left photo shows decay circled in yellow and then the finished results, with a good blend without a white line or too much polymerization shrinkage and with general integration into the tooth. The lower left shows a mesial, occlusal, and distal (MOD) filling. It has a uniform appearance throughout, without clear or transparent hue from any shadowing. Particularly in the smile zone, the composite must match to the tooth and offer good flexural strength and resistance to debonding. In the dark-shade case (Figure 5), the patient was older and since practitioner lacked a variety of dark shades in inventory, a universal that could give a dark appearance was used and a blocker was not necessary. The esthetic effect was superb and required minimal chair time.

Cementing Indirect Restorations

Types of cements include zinc phosphate, zinc carboxylate, glass ionomer, resin-modified glass ionomer, self-adhesive resin, and adhesive resin. New universal cements combine the abilities of the latter two. Examples of universal cements that are self-adhesive include RelyX Unicem 2 by 3M, Maxcem Elite Chroma Universal by Kerr, and Calibra Universal by Dentsply Sirona.

Indications for an indirect restoration are to restore form, function, and esthetics, and to reestablish structural integrity compromised by large restorations, decay, fractures and cracks, and root canals.5,6

Clinicians select a cement based on the procedure. Factors to consider include what restorations and substrates are indicated, how much bond strength is needed, and retentive vs. non-retentive preparation design; pair self-adhesive cement by itself with retentive preps and add universal bonding adhesive to non-retentive preps. The practitioner must know where they want to end before they begin.

Restoration types include veneers; full-coverage (crowns/bridges), whether tooth-supported or implant-supported; inlays/onlays; Maryland bridge; and post-and-core, fiber vs. metal (prefabricated vs. cast). Substrates include metal/porcelain fused to metal (PFM)/titanium implant abutments; zirconia/porcelain fused to zirconia (PFZ); lithium disilicate; glass ceramics; composite/fiber; and hybrid materials, such as lithium silicate reinforced with zirconia. As materials change, practitioners need cements that can keep up and bond well to everything-true universal cements.

Adhesive and Self-Adhesive Resin Cements

Resin cements are categorized by the polymerization action (light, chemical, and dual-curing) and the mechanism of adhesion (adhesive or self-adhesive). This article now will focus mostly on self-adhesives.

Clinicians select a cement based on the procedure. All adhesive resin cements require the practitioner to prepare the restoration and tooth with a specific primer and/or bond. Self-adhesive resin cements do not require the practitioner to prepare the tooth; however, depending on the cement being used, the substrate may need to be treated. Nonetheless, etching, priming, and bonding the tooth structure will yield higher bond strengths.7-9 These concepts, steps, and processes are generated by each manufacturer and are listed out in the instructions for use. Manufacturers are increasingly expected to combine the features of both adhesive and self-adhesive cements in a universal.

Indications for adhesive and self-adhesive resin cements include the need to control set time with a light-curable medium and the desire for optimum bond strength and maximum esthetics, as these products come in multiple shades with superior color stability.

Conditions and limiting factors within preparation design will dictate the type of cement to use. Whether the restoration is in the anterior or posterior will determine how much color stability and color control matters.10 The practitioner also must determine: will the margin be supra- or sub-gingival? Can the area be isolated well with good fluid control (for blood and saliva)? That is important for a stable bond. Will the preparation be retentive or non-retentive? Can it be accessed with a curing light? Is it compatible with the bonding agent, and is a separate activator required?

With retentive vs. non-retentive preparations, various factors dictate preparation design such as tooth position and location, material selection, existing restoration(s), decay, missing tooth structure, trauma, fractures, and clinician preference.11-15 Retentive preparations allow for both mechanical retention (friction between the tooth and the material) and chemical retention (adhesion), thus producing a chemo-mechanical bond. Maximum retention is achieved when the preparation has parallel walls.16,17 The ideal taper is 6 degrees, which may be difficult to obtain when tooth structure is missing or compromised.18

Non-retentive preparations are completely reliant upon the chemical bond, therefore requiring a strong adhesive cement and bonding agent.17,19

Types of preparations include equi-gingival, supra-gingival, and sub-gingival. Marginal adaptation and seal are critical. The same factors that affect preparation design will influence or determine whether the margin is finished supra-gingivally or sub-gingivally. Achieving isolation and moisture control can be difficult, but they are essential for successful cementation.16

The practitioner must consider how to prepare the restoration before cementing. Most other adhesive resin systems require several steps depending on the substrate and clinician preference. Should it be milled in the laboratory or in-house? Must the substrate be micro-etched, should hydrofluoric acid be used, or should a combination of etching and priming product be employed? Should a cleaning paste be added to eliminate the phosphates? Should a primer be applied for increased bond strength or should it be silanated, and is the addition of a bonding agent necessary? Bond can add film thickness and harm the fit, and all of the steps are technique sensitive and can add time, expense, and frustration. A universal, however, may allow the practitioner to skip several steps because of the cement's chemistry. Dentistry will begin to see a trend in universal resin cement materials with a unique chemistry that combines and/or eliminates the need for many of these traditional steps, similar to that of newer generation bonding agents compared to early-generation bonding agents. For example, the need for substrate primers, silane, and bonding agents will no longer be required to pretreat the substrate.8

In some scenarios, an adhesive or self-adhesive resin cement is contraindicated: when stable isolation and/or moisture control cannot be achieved, when esthetics are not a consideration, when mechanical retention is present, or when fluoride or calcium release is desired. In those cases, clinicians should opt to use a resin-modified glass ionomer (RMGI) or bioceramic cement instead.8,20,21

Bonded resin cements require a bonding agent and are the most technique sensitive and protocol heavy, but they have the best mechanical properties and are highly esthetic.8,22 Self-adhesives do not require a bonding agent and have an easier workflow and good mechanical properties and esthetics.8,23About 29% of dentists use a self-adhesive, 29% use RMGI, 26% use bonded resin, and 16% use something else.24

Many companies are trending to consolidate their adhesive and self-adhesive resin cement categories to simplify the practitioner's workflow.

For cementing in self-cure mode, look for a cement that can be cured in any modality and that does not require an additional catalyst with the preferred bonding system. The chemical curing reaction is extremely important when cementing a substrate in a situation where the curing light cannot reach or the light cannot penetrate the substrate.25This also is important because film thickness may be a concern-some bonding agents' film thicknesses may be higher than others and it is best to avoid adding another activator. Increased material film thickness and viscosity, whether on the substrate surface or on the tooth surface, may prohibit a restoration from being seated fully and result in failure to achieve a marginal seal. It may also result in requiring increased force to seat the restoration, which may in turn cause thin and fragile ceramics to become damaged or fracture. Cements from some manufacturers use a universal catalyst because their dentin bonding agents inhibit the curing of the self-cure portion of a dual-cure resin cement.26 Proper handling of the cement is crucial. Residual cement can cause crown failure, soft tissue inflammation, gum recession, peri-implant inflammation, and peri-implantitis (Figure 6).27-30

Post-and-core preparations and restorations can be difficult if the practitioner must employ multiple materials, add a catalyst, and have a separate core. Look for a cement that streamlines the post-and-core restoration process by featuring root canal tips that facilitate easier cementing of the post in the canal, offering dark-cure capability allowing full polymerization for optimal bond strength when cementing the post, and that can be used as a core build-up material, flowing well with minimal slumping and no voids, and that cuts well.

Compatibility is important, as practitioners work with various types of restorations and must match to existing, adjacent restorations. A universal that offers high bond strength with indirect restorations-including those made of zirconia, gold, rexillium, lithium disilicate, porcelain, composite, and/or titanium-is desirable.31

Case Studies

Figure 7 shows the day of delivery in a case in which a patient had undersized laterals compared to the rest of her teeth, so the practitioner added porcelain veneers on teeth Nos. 7 and 10. The practitioner did a prepless veneer employing a total etch technique and cemented with a universal.

Another patient presented with veneers approximately 15 years old, and the cement color had darkened over the years. The clinician applied four veneers from teeth Nos. 7 and 10 that resulted in excellent esthetics, proving the practicability of using a universal on anteriors.

In the next case, the practitioner used a zirconia crown to replace an e.max crown on tooth No. 23 that had brown staining/discoloration. The practitioner used a universal to place the zirconia crown. Excellent gum tissue health also was a result.

Another patient presented with composite buildups on teeth Nos. 7 and 8, which were narrow and small. The clinician replaced them with zirconia crowns. No matter the substrate and type of restoration, a universal is indicated.

The next case was particularly challenging as the patient was congenitally missing tooth No. 10 and had an undersized lateral tooth No. 7. A different practitioner had placed an implant too high, presenting challenges with the gum. The patient declined tissue conditioning or training, adding to the difficulty of the case. The practitioner cemented a veneer and did a custom abutment, using a universal cement to bond to the enamel of No. 7 and to the titanium at No. 10. Cement offered easy cleanup and was radiopaque, allowing the practitioner to make sure no cement was left behind, which could cause peri-implantitis.

The girl in Figure 8 broke tooth No. 9 at school and came into the dental office with 30 minutes left in the workday. The practitioner did a zirconia crown on the tooth. Use of the universal allowed ease in material selection and cleanup, and good gingival health.

For the case in Figure 9 through Figure 11, the patent presented for an initial consultation with bonding completed on teeth Nos. 7 through 10 a few years prior with a chief complaint of not liking the way the resin bonding looked and how it was wearing. Up to this point, the bonding had repeatedly chipped and been repaired three times already. The patient's canines also exhibited signs of incised wear and flattening, which she did not like. Based on the patient's goals for her smile and her financial budget, she elected to have porcelain veneers completed on teeth Nos. 6 through 11. The total esthetics of the case design were somewhat limited given that the patient's esthetic zone included her posterior teeth and mandibular anterior teeth. Therefore, the color and characteristics of the veneers had to match her existing dentition closely.

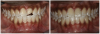

In another case, the patient presented with very thick, bulky, over-contoured veneers done on teeth Nos. 7 through 10 when she was a teenager. There also was some recession and staining at the margins (Figure 12). The clinician decided to restore teeth Nos. 6 through 11. A preparation design was required with provisionals removed. As tooth structure could not be regrown, the practitioner made the best of the situation. There was good gum health, which is important for isolation and marginal seal. The clinician cemented with a universal, doing six units at one time. Minimal cleanup was required. At a 1-month follow-up visit, although tissue still was settling in, the contours were natural. After a year (Figure 13), the gum filled in nicely and was in excellent health, and there was good color stability and seamless marginal integrity.

Efficacy of New Universal Resin Cements

The new universal resin cements allow bonding to e.max, zirconia, metal, glass ceramics, and fiber posts without changing the protocol. They can be used with or without a bonding agent depending on the preparation and the amount of bond strength needed, and they require only one cement without the need for special cements. Universal resin cements bring simplicity and flexibility into a typically complex and technique-sensitive bonded resin procedure, and let the clinician use any bonding agent he or she prefers, with a simplified inventory. The cements allow the dentist to choose the bonding agent of his or her choice, without having to pair the manufacturer's bond with its cement.

Bonding agents now are in their eighth generation. These nano-bonding agents are solutions of nano-fillers, which produce better enamel and dentin bond strength, stress absorption, and longer shelf life.32 Eighth-generation bonding agents are less technique sensitive and therefore easier to use, with increased predictability. They consolidate steps and materials, and bond to substrates, both direct and indirect. This increases efficiency by saving time and reducing the amount of inventory needed, because now one adhesive is sufficient. Examples are 3M Scotchbond, Dentsply Sirona Prime and Bond Elect, Ivoclar Vivadent Adhese, and Kerr Optibond. Practitioners can self-etch with no phosphoric acid; selective-etch with phosphoric acid on enamel; and perform a total-etch with phosphoric acid on enamel and dentin.

Contact angle and resin penetration are important, as they relate to wettability and bonding, and universal bonding agents provide proper penetration.30,33-35 Indicated is a low-film-thickness bonding agent that is hydrophilic on the tooth side-so it penetrates and gets taken up into the tooth structure-but is hydrophobic on the resin side for bonding strength. A bonding agent with good hydrophilic characteristics will have good penetration into the dentin and strong adhesion.36,37 Most dental materials, including dental resin cements and dental composite resins, are hydrophobic. The wetting angle can determine whether there is no, minimum, or maximum resin penetration (Figure 14). Insufficient resin penetration leads to post-operative sensitivity and the potential for having to redo restorations. Film thickness is important to consider, especially during cementation, and can range from 3 to 10 μm depending on the manufacturer.38-41

Conclusion

Universal materials provide many benefits that can help practitioners achieve excellent outcomes consistently, regardless of technique. They allow for a simplified treatment approach, which reduces chair time and overhead expenses. In a time in which COVID-19 has caused PPE and many other operating costs to rise, having a consolidated inventory and efficient treatment protocols can help offset this financial burden. Furthermore, decreasing the patient chair time lowers the potential risks for exposure to COVID-19.

References

1. Davidson MW, Abramowitz M, Parry-Hill MJ, et al. Molecular Expressions: Science, Optics and You - Specular and Diffuse Reflection: Interactive Java Tutorial. https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/primer/java/scienceopticsu/reflection/specular/index.html. Published 2015. Accessed October 27, 2020.

2.Rakhmatullina E, et al. Application of the specular and diffuse reflection analysis for in vitro diagnostics of dental erosion: correlation with enamel softening, roughness, and calcium release. J Biomed Opt.2011;16(10):107002.

3.Pereira Sanchez N, Powers JM, Paravina RD. Instrumental and visual evaluation of the color adjustment potential of resin composites. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2019;31(5):465-470.

4.Tsujimoto A, Barkmeier WW, Fischer NG, et all. Wear of resin composites: Current insights into underlying mechanisms, evaluation methods and influential factors. Japanese Dental Science Review.2018: 54(2):76-87.

5.Azeem RA, Sureshbabu NM. Clinical performance of direct versus indirect composite restorations in posterior teeth: A systematic review. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21(1):2-9.

6.Skjold A, Schriwer C, Øilo M. Effect of margin design on fracture load of zirconia crowns. Eur J Oral Sci. 2019;127(1):89-96.

7.Johnson GH, Lepe X, Patterson A, Schäfer O. Simplified cementation of lithium disilicate crowns: Retention with various adhesive resin cement combinations. J Prosthet Dent. 2018;119(5):826-832.

8.Fialkoff S. The perfect match: Selecting the most appropriate material and cement. Inside Dentistry. 2020;16(3): 18-30.

9.Powers JM, O'Keefe KL. Cements: How to select the right one. Dent Prod Rep. 2005;39:76-78,100.

10.Turgut S, Bagis B. Effect of resin cement and ceramic thickness on final color of laminate veneers: An in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 2013;109(3):179-86.

11.Winter R. Factors that will influence anterior preparation design, Part I. Spear Education Online. July, 13, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.speareducation.com/spear-review/2015/07/factors-that-influence-anterior-preparation-design-part-i

12.Winter R. 10 factors that will influence anterior preparation design, Part II. Spear Education Online. August, 10, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.speareducation.com/spear-review/2015/08/10-factors-that-will-influence-anterior-preparation-design-part-ii

13.Goodacre CJ, Campagni WV, Aquilino SA. Tooth preparations for complete crowns: an art form based on scientific principles. J Prosthet Dent. 2001 Apr;85(4):363-76.

14.Vianna ALSV, Prado CJD, Bicalho AA, et al. Effect of cavity preparation design and ceramic type on the stress distribution, strain and fracture resistance of CAD/CAM onlays in molars. J Appl Oral Sci. 2018;26:e20180004. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0004. Epub 2018 Aug 20.

15.Ön Salman G, Tacír ƔH, Polat ZS, Salman A. Influence of different cavity preparation designs on fracture resistance of onlay and overlay restorations using different CAD/CAM materials. Am J Dent.2017 Jun;30(3):165-170.

16.Cardoso MV, de Almeida Neves A, Mine A, et al. Current aspects on bonding effectiveness and stability in adhesive dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2011;56(Suppl 1):31-44.

17.Tripathi S, Amarnath GS, Muddugangadhar BC, et al. Effect of preparation taper, height and marginal design under varying occlusal loading conditions on cement lute stress: A three dimensional finite element analysis. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2014;14(Suppl 1):110-8. Epub 2014 Jul 10.

18.Adarve RM. Advance dental simulation: Module on crown preparation. University of Minnesota School of Dentistry. November 19, 2008. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.dentistry.umn.edu/sites/dentistry.umn.edu/files/ module_on_crown_preparation.pdf

19.Helvey GA. Non-retentive, adhesively retained all-ceramic posterior restoration. Inside Dentistry.2011;7(2):38-50.

20.Fagin MD. Taking the mystery out of cementation decision making. Dental Economics. April 19, 2016. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.dentaleconomics.com/science-tech/article/16388137/taking-the-mystery-out-of-cementation-decision-making

21.Lowe RA. Dental cements: An overview. Dentistry Today. October 6, 2011. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://www.dentistrytoday.com/dental-materials/6151-dental-cements-an-overview

22.Blatz MB, Vonderheide M, Conejo J. The effect of resin bonding on long-term success of high-strength ceramics. J Dent Res. 2018;97(2):132-139.

23.Makkar S, Malhotra N. Self-adhesive resin cements: A new perspective in luting technology. Dent Update. 2013;40(9):758-78.

24.Kerr internal data.

25.Dehghan M, Braxton AD, Simon JF. An overview of permanent cements: What a general practitioner needs to know to select the appropriate dental cement. Inside Dentistry. 2012;8(11). https://www.aegisdentalnetwork.com/id/2012/11/an-overview-of-permanent-cements

26.Osman SA, McCabe JF, Walls AW. Film thickness and rheological properties of luting agents for crown cementation. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2006;14(1):23-7.

27.Quaranta A, Lim ZW, Tang J, et al. The impact of residual subgingival cement on biological complications around dental implants: A systematic review. Implant Dent. 2017;26(3):465-474.

28.Hughes K. Implant failures caused by cements: Salvaging compromised cases and preventing complications. Inside Dentistry. 2013;9(2). https://www.aegisdentalnetwork.com/id/2013/02/implant-failures-caused-by-cements

29.Pauletto N, Lahiffe BJ, Walton JN. Complications associated with excess cement around crowns on osseointegrated implants: a clinical report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14(6):865-8.

30.Korsch M, Walther W, Bartols A. Cement-associated peri-implant mucositis: A 1-year follow-up after excess cement removal on the peri-implant tissue of dental implants. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2017;19(3):523-529.

31.Brown W, et al. Bond strength of several self-adhesive cements to enamel and dental. IADR.2015.

32.Sofan E, Sofan A, Palaia G, et al. Classification review of dental adhesive systems: From the IV generation to the universal type.Ann Stomatol (Roma). 2017;8(1):1-17.

33.Toledano M, Osorio R, Moreira MA, et al. Effect of the hydration status of the smear layer on the wettability and bond strength of a self-etching primer to dentin. Am J Dent. 2004;17(5):310-4.

34.Mehtälä P, Pashley DH, Tjäderhane L. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide on dentin collagen. Dent Mater. 2017;33(8):915-922.

35.Yamauchi S, Wang X, Egusa H, Sun J. High-performance dental adhesives containing an ether-based monomer. J Dent Res. 2020;99(2):189-195.

36.Abdelsalam R. Fluid contact angle assessment to evaluate wetting of dental materials. East Carolina University. May 2017. Accessed November 15, 2020. https://thescholarship.ecu.edu/bitstream/handle/10342/6147/ABDELSALAMMASTERSTHESIS-2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

37.Papadogiannis D, Dimitriadi M, Zafiropoulou M, et al. Universal adhesives: Setting characteristics and reactivity with dentin. Materials (Basel). 2019;12(10):1720.

38.Muñoz MA, Sezinando A, Luque-Martinez I, et al. Influence of a hydrophobic resin coating on the bonding efficacy of three universal adhesives. J Dent. 2014;42(5):595-602.

39.Betancourt DE, Baldion PA, Castellanos JE. Resin-dentin bonding interface: Mechanisms of degradation and strategies for stabilization of the hybrid layer. Int J Biomater. 2019;2019:5268342.

40.Hirata K, Nakashima M, Sekine I, et al. Dentinal fluid movement associated with loading of restorations. J Dent Res. 1991;70(6):975-8.

41.Brännström M. Etiology of dentin hypersensitivity. Proc Finn Dent Soc. 1992;88 Suppl 1:7-13.